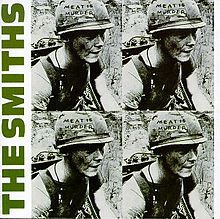

Originally released on February 11th, 1985. A version of this review was published on April 1st 2007.

Author’s note: I have spent lots of time over the years pointlessly debating which one of The Smiths albums was “the best”. Morrissey’s view is that Strangeways, Here We Come was the band’s apex, many fans argue for The Queen Is Dead, whilst Hatful of Hollow is also widely regarded as superior to their debut. Meat Is Murder was their problem child, one in which Johnny Marr’s casual virtuosity was to the fore, turning his hand to anything which took his fancy, with stunning results. It was their only number one – not that this means a great deal – and Morrissey has subsequently admitted that Barbarism Begins At Home was his least favourite Smiths song. But still. Music is about time and place as much as notes and melody. It’s a largely personal experience, one that prompted me to more than twenty years later pen this furious defence of Meat Is Murder in the face of so much popular and critical rhetoric.

The general belief is that “Meat is Murder’s” successor; “The Queen Is Dead” was the magnum opus of Morrissey and Marr’s creative kernel: this is wrong. The latter contains all the hallmarks of The Smiths’ gargantuan creative impetus; a mordantly romantic sense of pathos, the darkly humorous lyrical sang-froid, misanthropic humour and simple, reduced emotions of real people. The squealing jackhammer of the title track raged, vomiting republican bile across the monarchist herds, the beautiful ache of “I Know It’s Over” and the pseudo pubescent wistfulness of “There Is A Light That Never Goes Out” were amongst their most crafted and poignant songs. All this matters. However, Meat is Murder is superior.

I’ll explain why. Firstly, it was recorded across the harsh, freezing winter of 1984 against a backdrop of a nation being torn apart by an industrial dispute rooted in all of Britain’s post war class prejudices, where the largely northern, socialist coal miners had engaged in a winner-takes-all de facto civil war with the ruthless, uber-capitalist government of Margaret Thatcher. Morrissey would leave direct references to the right wing ideologue until Viva Hate, but despite lacking the over political references of a Bragg or Weller, an overwhelming darkness still gnawed here at the edges; by any standards, Meat is Murder is an angry record, far more polemical than any other The Smiths made.

Secondly, it’s rich in musical as well as lyrical diversity. Johnny Marr’s neo-classicist guitar work was never better, taking you to places of light and shade via country, funk and classic rock and roll via an insouciant wink to Elvis. Morrissey’s acerbic and coruscating ire was it’s counterpoint, railing at subject matter as diverse as the melodic backdrop. No-one was safe – the exploded myth of Mr Chips (The Headmaster Ritual), the disaffected savagery of youth violence (Rusholme Ruffians) or the celebrated vilification of domestic thuggery (Barbarism Begins At Home). It’s an album without a nanosecond of filler, each riff, each word as important as the ticking clock.

By any standards for the key players it was a transformational experience. Prior to it’s release Morrissey was regarded in certain quarters with suspicion and disdain; his apparent polysexulaity (framed by abstention), the hearing aids, the gladioli and the women’s shirts seemingly constituting a kind of parlour joke on a music industry obsessed with image. After The Smiths were critically acknowledged as the most gifted and influential British band since The Beatles, not quite an institution by that point, but a unique medium through which many of the country’s cultural idiosyncracies were filtered at arm’s length.

Now slightly blunted by familiarity and endless plagiarism it’s still capable of delivering fascination – “The Headmaster Ritual” stings like being strafed across the back of the calves with a wooden ruler, “That Joke Isn’t Funny Any More” isolates and plunges you into despair, “Barbarism Begins At Home” showcases the frequently overlooked, beat-perfect rhythym section of Joyce and Rourke, whilst “Well I Wonder” has you longing for that him or her in a ferment of crass hormonal romanticism.

Meat is Murder was the point where cerebral met celibate and the social, political and cultural ley lines of this island nation were united under a flag of The Smiths’ convenience. At the time, most other things seemed pointless.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.